March 30 1960: 30,000 Africans march on Cape Town, eight miles from the African townships. They head for Parliament but detour to the Police headquarters at Caledonian Square when they hear that the army has surrounded it. It is a call to end the pass laws.

September 13, 1989: 30,000 South Africans of all races march on Cape Town, from St. George’s Cathedral to the Cape Town Parade. It is called a Peace March. It is a call to end the violence The first contributed to my leaving South Africa. The second contributed to my ability to return.

The 1960 march takes place nine days after the notorious Sharpeville massacre. It’s leader is arrested. It results in the declaration of a State of Emergency that very afternoon, and the brutal clamping down of political activists for years and decades to come. The 1989 march, twenty-nine and a half years later, is lead by Archbishop Tutu. Five months later, almost to the day, apartheid unravels. Nelson Mandela is released and the ANC and PAC were unbanned. The dismantling of the apartheid state began. Four years later, in April 1994, Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as the first President to represent all the people of South Africa.

I walk into the newly opened exhibition space in the crypt of St. George’s Cathedral.

I stop before towering photos capturing the 1989 march. The role that the religious leaders, Christian and Muslim, provided gravitas to the event and are in the forefront. Being Jewish, I note the absence of Rabbis. The Chief Rabbi of Cape Town was initially against the march, I am told, but supported the actions later. It was sparked by the killing of 23 people in various Cape Town townships in the aftermath of the second tri-cameral parliament elections on Election Day, six Days earlier.

Enough!

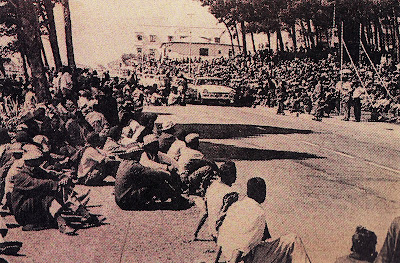

Photo by Eric Miller (www.eric.co.za) who kindly agreed that I place it in this blog.

I am moved, emotions wrenching, tears well up as I see a dense mass of thousands upon thousands of Capetonians, black, white, men, women, young, old, in business suits with ties, in shirt sleeves and t-shirts, serious faces, smiling faces, somber faces, glowing faces. Faces of a people who know they are winning.

I recently found black and white grainy photos of the first march. They are equally powerful. African men, and some women, packed tight as they walk silently into the centre of the city. I reflect that, looking back, way back, what happened that day lead to my leaving. It is why I am not a face in the crowd in the photos in St. George’s Cathedral crypt.

The march came nine days after the March 21st Sharpeville massacre which captured headlines throughout the world. The protest was part of a wide campaign against the pass laws. These laws forced all Africans living in urban areas to carry pass books in the land of their birth to prove that they had permission to be there. These laws defined every movement and aspect of their lives. Relegating them to no more than units of labor, they provided a Draconian means of controlling and directing a cheap – very cheap - labor force. The pass laws were one of the main pillars of apartheid and the fuel for a vibrant South African economy. In 1952, four years after the apartheid government came to power, the laws were extended to include all male Africans over the age of 18 regardless of whether they lived in the towns or the rural areas; four years later African women were lassoed into the law.

Enough!

The call went out: Leave your passes at home, present yourself to your local police station and be arrested. Township after African township throughout South Africa responded to this call. In Sharpeville, the cheerful, calm and friendly protestors sent jitters down the spines of the skittish police, young and inexperienced. They fired wildly into the crowd. Most of the victims were shot in the back while trying to flee, including ten children, some on the backs of their mothers. The killings caused reverberations around the world, bringing with it unprecedented shock and horror at the extent of the brutality of the apartheid regime, which up until then the world had largely managed to tolerate and ignore.

The protests were local within the confines of the proscribed African areas that the police could contain.

Not so Cape Town.

The specter of 30,000 Africans walking deliberately and silently out of the townships of Nyanga, Langa and Gugulethu scared the bejeebies out of the white government.

As well as for many of the soldiers deployed to provide control.

Michael Mittag, a friend from university and beyond, stood outside his office on one of the streets leading into the city center. “There was a buzz, an eerie buzz, that reverberated through the buildings. It sounded almost electronic”. He was impressed. In awe. But not the terrified soldier no more than 18 years old standing near him, who gave visible evidence to his fear by the spreading wet spot in the front of his pants.

At the head, dressed like a school boy in shorts and sockless shoes – the only clothes he possessed - was Philip Kgosana, looking even younger than his scant twenty-three years. He had hoped for a turnout of about 5,000. Kgosana, having acquired the necessary white sponsorship was among the few African students permitted to attend the University of Cape Town. The only way he could support himself was to live in the all male sub-standard barracks built for grossly underpaid ‘migrants’ (foreigners in their own country) as ‘temporary’ (they were in fact permanent) housing far away from their wives and families in the rural areas who were not permitted to live with them. Steeped in their lives, their histories, sufferings and living conditions, Kgosana dropped out of university and began working as a political activist full time.

Kgosana fearful that the police would begin to fire and cause life-threatening havoc and among the marchers tightly packed in the narrow streets of Cape Town, agreed to ask the marchers to return home. But only after he was promised an interview with the Minister of Justice so that he could place the demands of the marchers before him. On Kgosana’s his request which travelled back through a murmuring wave from the front of the protest to the back, they turned around as one and walked back to their townships, led now by police vans.

At four o’clock Kgosana arrived for the meeting. He was arrested. Nine months later he was released on bail. He skipped the country and went into exile. (He is now back home)

I was in my last year of high school, and our school, like most probably most, went into virtual lock down. It was considered a dangerous situation.

The evening of the march my father, Joe’s step through the back yard was uncommonly quick and light, lacking any of his usual end-of-day draggy tiredness. He was positively glowing. No sooner had the news of the march spread to him in his law office in Athlone, a Coloured area of Cape Town, he was in his car driving to a vantage point to view the extraordinary phenomenon. He was awe struck by the huge, silent, orderly march of thousands upon thousands of determined Africans, who with immense dignity walked towards the center of Cape Town with their one message. It was a demonstration of power and of determination that he had never before witnessed or believed possible and he was exhilarated.

“This is the beginning of the end!” he announced at the dinner table to my mother, my sister and I and perhaps our African domestic worker listening from the kitchen. “The government cannot deny what has just happened. The passes have to go.” He truly believed that this was a major turning point, from which there would be no going back. What he saw when he surveyed the dense protest, was a determined mass of African workers taking up the struggle, flexing their collective muscle, and showing the oppressive ruling class that they were ready to take on the revolution. His Trotskyist viewpoint was being justified. The workers had risen. There could be no turning back. Or so, on that day, he fervently believed.

He underestimated the might of the apartheid machine.

A State of Emergency was declared that afternoon. Within days the Unlawful Organizations Act was passed, the ANC and PAC were declared illegal. The Terrorism Act was passed, which allowed for indefinite detention without trial. The Communism Act were more stringently enforced. A severe clamp down followed of all who might be considered a danger to the state. Thousands were arrested. Thousands fled into exile.

Thousands fled into exile.

For the next eight or nine years, South Africa experienced a hiatus in open political activity. Caught in the revolution’s doldrums as a result of terrible and mounting repression, looking on as bannings and detention without trial and trials for “crimes” that were simply demands for human rights were metered out with determination by an state bent on crushing any resistance, however slight, I decided to leave.

This was not an easy decision, and the discussion, and debates and differences with friends who decided they must stay often went on into the night. But with heavy heart I made it along with others who were privileged to be able to leave voluntarily into self-exile at our own pace. I simply could not live under apartheid, benefit from its privileges because of the happenstance that I was born into the “white” racial category, and while finding no obvious – for me at the time - meaningful way to contribute to change.

After leaving the exhibition I was invited to have lunch with the Cathedral’s Sub-Dean Fr. Terry Lester, Lynette Maart and Josette Cole.

Fr. Lester, Maart and Cole are social justice activists of the 1980s generation who are passionate about educating next generations about what happened under apartheid in general and the role the St. George’s Cathedral played in pursuing non-violent means of struggle in particular.

Fr. Terry Lester and Lynette Maart are part of the leadership team of the St. George’s Cathedral Crypt Memory and Witness Centre. The Centre aims to excavate the social history of the Cathedral, particularly its role in the struggle against apartheid to use as a lens to current social justice issues. Josette Cole, a member of the Mandlovu Trust, is researching the struggles of squatter communities in and around Cape Town between 1977 and 1985. Plans for the next exhibition are well underway. Under the theme ‘Bearing Witness’ it will focus on the 23-day fast in March/ April 1982 of 57 Nyanga Bush squatters at St. George’s Cathedral to protest the dire lack of rights for Africans to live - as families - and work in Cape Town/Western Cape.

Our conversation is as inspiring as it is sober. They do so with zeal and purpose. I listen to their plans and can only be impressed.

But as I listen I reflect that Brecht’s words about the “difficulties of the plains” are all too real.

They talk about how Cape Town was being transformed into a city for foreigners, for tourists to enjoy.

They talk about Cape Town being gradually transformed into a city for foreigners, for tourists to enjoy.

They talk about resources being poured into making the centre of Cape Town safe and beautiful, a magnet for the privileged.

They talk about lack of access to resources for those who continue to live in poverty on the Cape Flats in areas apartheid relegated to coloured and African people.

They talk about how those continuing to live in these inhospitable outskirts of the city are most likely to remain, given Cape Town’s exorbitantly high property rates.

They talk about iron shacks, and crowded tiny brick houses, and lack of water and lack of electricity; of inferior education.

They talk with concern about what they see as a the lack of political will to forge change, so that for too many what they had marched for, what people by their thousands had died for is still in the realm of dreams.

I listen and I find I am listening as an outsider.

I know, and knew, that the South Africa I would return to, would be a complicated and often distressing place.

I am listening to a story that is not directly mine. Not yet. Without living here, without being engaged is specific aspects of working for change, can I, I wonder, I regard South Africa as home?

But ‘home’, I know is a fluid and often mercurial concept. It can be attached to more than one place and space. But this is for a future blog.

Meanwhile, I am moved by the history of struggle in South Africa, inspired by the tenacity of those who lived through it and won. I am moved in a way that is only possible because I was born here. And because growing up in Cape Town and South Africa defined who I would then become. I was raised and socialized here so that what I now see and recognize became as intrinsic to me as any part of my genetic makeup.

And I cannot give it up or give up on it.

But as I said, this is for a future blog, as I continue to mull over the meaning for me of the triumvirate of words: exile, nostalgia, home.

Eric Miller is one of the most widely published and experienced photojournalists working in South Africa who documented the anti-apartheid struggle and continues to document the process of transformation in South Africa.

Cape Town March 2, 2011