Clifton beach at sunset

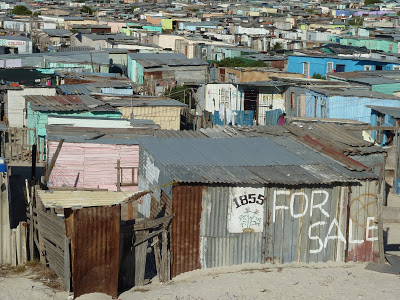

There are significant ways that South Africa looks after its poor that puts the US to shame. Take the story of Grace, who’s name matches her personality. I got to know her when I stayed at a friend’s house where she works as a domestic worker. Last September Grace had a double bi-pass surgery at Groote Schuur hospital, no longer the segregated hospital of apartheid years, whose standard of medical care was spotlighted when Christiaan Barnaard performed the first heart transplant in 1967. The cost? Completely free. That’s not all. Grace was able to build her own house using a subsidy from the government, supplemented by aid from the Irish government. In addition, she received receive monthly social grants that are provided to all families with children under the age of 18 who qualify according to an income based means test. When Grace reaches the age of 60 she will qualify for a state old age pension that is not tied to any form of contribution while working.

RACISM

Ongoing racism is often raised as a reason for not living here, I understand how strong the response is for those who see it. Because of our past, because of growing up under apartheid, the reaction to racist incidents is like a punch in the belly. A really hard punch. For me, though, having lived these many years in the United State, it’s a no go argument. There racism is rampant, a constant undercurrent of life and politics, of the economy and society in general. A black President has not meant that racism is over, although some seemed to want to argue this. It has meant all too often that a backlash has been severe. And since 9/11 Americans of the Muslim faith have experienced levels of racism and xenophobia that is unprecedented.

I remember a comment by a close South African when she lived in New York for three years in the late 80’s studying at Columbia University, that she had never, ever in South Africa experienced the racism she encountered in the US, both as a white South African and as a general part of living in American society. Regard for white South Africans might have changed the day that Mandela became President, but the general level of racism remains.

I have been impressed over the past two months at the few racist incidents I have encountered and when I have they tend to be very mild. What I do observe is the systemic racism. Although I no longer feel my stomach clenching into a knot of discomfort to the point of pain when I enter a Cape Town restaurant and am confronted by the usually all white clientele, I haven’t stopped noticing. I have spent a lot of time in the past few days with a Somali friend and her 6-year-old daughter, Hibo, and we can only laugh as we note, once again, that they are consistently the only black customers.

Certainly there have been the open though not necessarily hostile stares, as I walked along Fish Hoek beach with Hibo. But these were less frequent than the smiles, the calls of “How beautiful!” and “I love your hair” (that day her long hair stood out in a magnificent mass of curls) and then “And yours too!”, from someone with the same grey curls as mine. People would stop to chat and to encourage Hibo to pet their dogs. When we were in restaurants or at Kirstenbosch (Botanical Gardens) the usual children seeking out children to play with took place and she was off to participate in their games, apparently fully accepted.

In my daily interactions with people on the street and with people I meet for my writing and for pleasure I am accepted with generosity and affection, regardless of race or class. And so after a while, I have found that this is what I anticipate. Color is not something I am noticing on a personal level. When I walk into white, white restaurants or shops I do notice. This was very different in Johannesburg. There is a much bigger black middle class in Gauteng (Johannesburg and Pretoria). The suburbs are not as segregated. Race meets class.

Back in the US I will once again encounter a pervasiveness of race.

COULD I LIVE HERE?

Quick answer: Yes.

This doesn’t mean I am going to return. There are too many other considerations at this stage of my life. The point is that I know I could live here and part of me would love to. Not to, feels a bit like a abandonment by the privileged of an ongoing struggle for change in this country which I have found at the community and civil society level to be inspiring.

Every now and then a thought nags at me that goes something like this: To have skills that one can bring to the vast need here, and not do so feels like an easy way out; to not be part of it, feels a bit like desertion. I do remind myself that poverty is systemic and exists everywhere. But for me, with my past of having grown up here, it would and it could make some sense to return, even at this late stage. That I don’t contemplate it except to spend some months here each year is personal. It has little to do with South Africa per se.

I think about what one South African friend wrote in her annual letter to friends on return to Johannesburg after seven years of working in New York. After commenting that people who didn’t know her well and some who did expressed delight and amazement that she would return home at a time when the country was once again in a cycle of middle class emigration, she wrote: “Of course I’m amazed anyone would think we’d stay away – rather this mess, our mess, one we understand, than the messes elsewhere – and yet another year of Obama’s own party not supporting him on health care, two wars unending, and a number of colleges suffering a shooting rampage, reminds one of how the grass may seem greener but every country has its madnesses.”

My problem is that BOTH the United States where I have lived for over 40 years and South Africa talk to me of their madnesses. I relate to two messes. So which one do I choose? It is a rhetorical question, as I have chosen to remain in the US.

BACK TO THE QUESTION OF ‘HOME’

Where is that illusive thing called home? Because of this blog and my current writing I am thinking about this a lot more than I ever have.

On Monday night I attended a Seder with some friends. It was a lovely evening. The discussion about freedom and the meaning of Passover allowed for thoughtful reflections. I sat amongst good people, One friend I have known since I was eight; the other since the first month of moving to New York. They have returned to live in Cape Town with their American husbands.

So why did I feel sad, emotional even? I was feeling as “home”-sick! I was missing the annual Seder that my family has been part of for the past twenty or so years in Montclair. And I felt almost teary.

Our Seder is an annual event, where we cook up a storm, invite friends, Jews and non-Jews and read from the pointedly secular Haggadah that one of the group prepared based on progressive Haggadahs that have emerged over the past decades.

I called after I got back to where we are staying, and was welcomed by shrieks of delight over the phone. Stephanie!!! I could hear the buzz of people in the background as they waited for Kendra, my daughter, to get there from the city after work so they could begin. How many are there this year, I asked? About 22, 23. Oh, I said, that’s small! Last year we had 31 squeezed around Claudia’s table. So I said, next year in.... Montclair. Home?

I continue to have difficulty in satisfactorily or at least not succinctly answering the question posed by the title of my blog. Home is where the heart is, goes the adage. My heart, I am finding is in many places.

In the United States my heart is with a wide group of very good friends, some South Africans, some Americans, a few hailing from other nations.

In London it is with close family members who either immigrated from South Africa around the time I did, or, as in the case of my niece and my great-niece, were been born. There as well as some true Brits besides my nieces, including my goddaughter – at least until she recently (happily or me, though perhaps not for her Mom) moved to New York.

In South Africa where I have friends who when we meet after often years of separation simply pick up on conversations we had before and expand. My heart is with these, my communities in different parts of the world. Home is not a static place for me. It is where I happen I feel at home. Most particularly it is where I feel passion and compassion.

Where I engage in debate, where I get affected by the politics and the news. In my case it takes place in both South Africa and the environs of New York if not the United States as a whole.

Perhaps I must simply echo Socrates, "I am not an Athenian (Capetonian), or a Greek (South African), but a citizen of the world." Or the Tamil poet, Kaniyan Poongundran who wrote, "To us all towns are one, all men our kin". Thomas Paine, "My country is the world, all men are my brethren and my religion is to do good." (I will forgive them their use of “men”)

Have I come home or back? I still don’t really know. I have come back to Cape Town. But home? I proudly tell people wherever and whenever the question arises, that I was born here but I live in the United States. Sometimes I will add “It’s good to be home”. I then may expand: “Growing up in South Africa means that the country continues to have a hold on me. South Africa will never let you go”. They all nod.

I was flagged down at 11:30 one night on the Main Road in Newlands on my way back from dinner with friends by two policeman, one black one white. The white came up to me and explained it was a spot check. He asked for my license. Ah, New Jersey! he said. I told him I was born here. He smiled as he said with great emphasis in a strong Afrikaans accent, “Ag, but South Africa is best! The very, very best!”

(He then cautioned me that they were concerned that I was driving alone at that time of night. It is dangerous he assured me. Up until that moment I was feeling particularly good about life, and independent. I drove the rest of the way to Tamboerskloof aware of every car behind me. But by the next day I felt unencumbered by fear once more, just aware of the sensible precautions to take as one does in both South Africa and New York, although in South Africa these precautions are far more stringent.)

CAN YOU LONG FOR A PLACE AND NOT CALL IT HOME?

I will miss South Africa when I leave. I will miss Cape Town which, before I came, I didn’t expect to feel as attached to as I now do. I will also long to return and get to know other parts of South Africa as I got to know Matumi. I miss the different terrain, the different sense of other parts of South Africa that resonate more closely with the other parts of Africa I got to know over the past decades. (See earlier blogs on Matumi and Maputo)